The History of Hygiene from Past to Present and a Fresh Approach to Hygiene

Hygieia Fountain, Hamburg. Photo: Daniel Schwen

While we now encounter the term “hygiene” more frequently in our daily lives due to the Covid-19 pandemic, exploring the word’s origins takes us back to the Ancient Greece. In this exploration, we come across Hygieia, the goddess of health and cleanliness, who is the daughter of Asclepius, the god of medicine, recognized by his serpent-entwined rod that has become the symbol of medicine. Hygieia was known for finding remedies for the ailments of both sick people and animals. Historical reports indicate that the cult of Asclepius and Hygieia gained widespread popularity in Greece and eventually worldwide during the 5th century BC, fueled by the devastating plague epidemic that swept through cities. Despite the eventual end of the plague, Hygieia has endured as a presence among people for centuries.

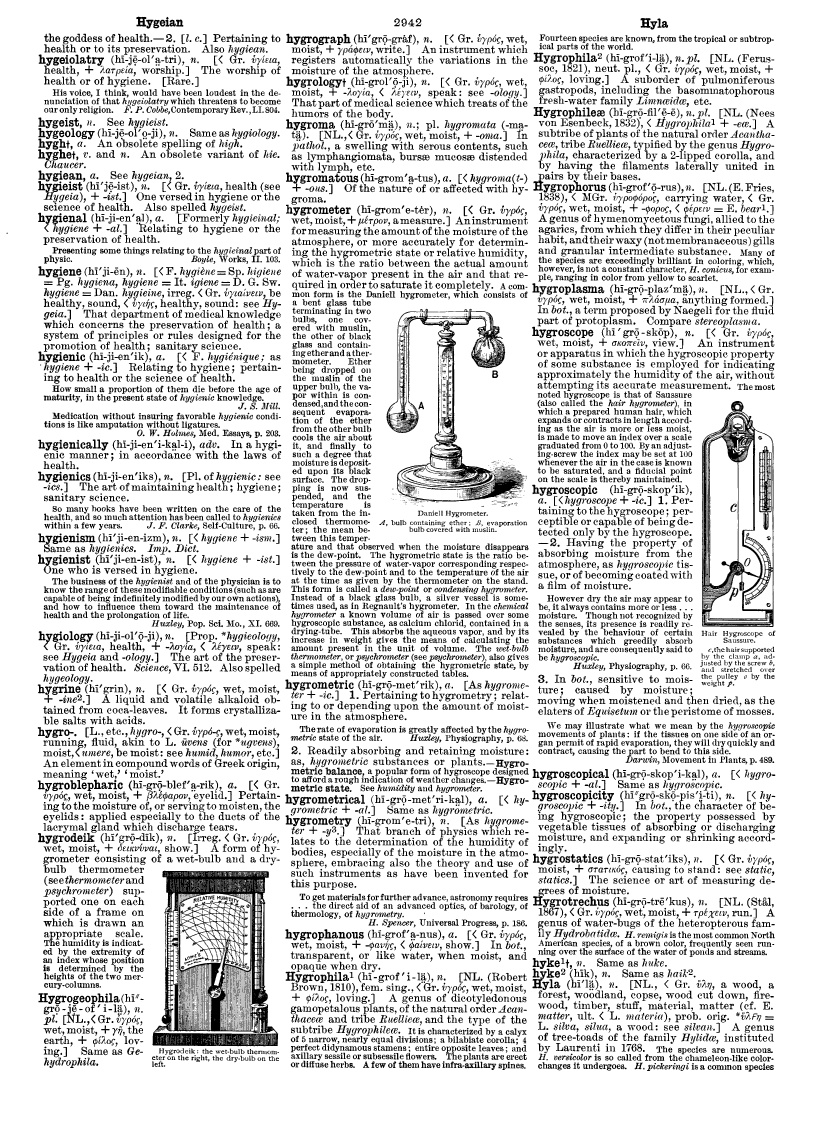

Century Dictionary, Vol. IV, Page 2942, Hygeian to Hyla Century Dictionary, Vol. IV, Page 2942, Hygeian to Hyla |

Today, we prioritize hygiene in nearly every aspect of our lives, encompassing the food we consume, the clothes we wear, the vehicles we utilize, and the spaces we inhabit. Examining the historical interplay between architecture, design, and cleanliness reveals one of the earliest examples in the form of drainage and cesspit systems dating back over 6,000 years, unearthed during the excavations of the Ancient Babylon.

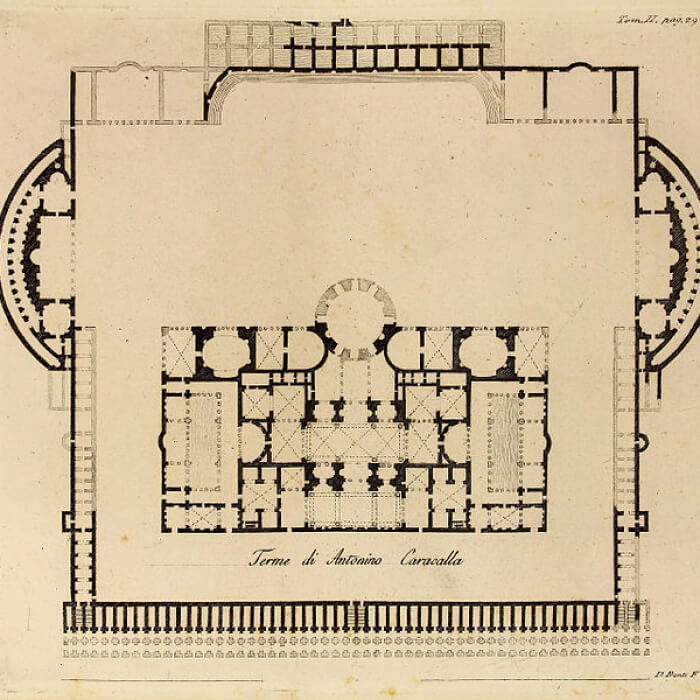

Archaeological findings from various parts of the world inform us about the existence of advanced plumbing systems dating back to the pre-common era. In the settlement of Mohenjo-Daro, in today’s Pakistan, around 2500 BC, an intricate system was employed to provide clean water and to manage sewage. The island of Crete boasted advanced plumbing systems, while the ancient Jerusalem featured both sewage and water supply systems. By the 200s BC, the Roman Empire pioneered water management through aqueducts and the use of lead pipes, distinguishing their approach from the other plumbing systems. Water sourced from mountains was collected in massive cisterns and transported via lead pipes to baths, public fountains, and residences. In the 600s AD, the Chinese, utilizing deep wells and bamboo reeds, accessed underground sources for drinking water.

Mohenjo-daro Baths (The Great Bath) |

Plan of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, Venuti, Ridolfino, 1705-1763 |

Baths of Caracalla |

Despite the existence of various plumbing systems, diseases and epidemics have ravaged cities throughout history when hygiene was insufficient. In 430 BC, in Athens, where adequate hygiene couldn’t be ensured despite water supply systems, waterways, public baths, and public toilets, approximately one-third of the population succumbed to the plague. According to some sources, Malaria, transmitted to humans by the Anopheles mosquitoes, played a significant role in the decline of the Greek Empire. Commencing in 1346 in China and Central Asia, the “Black Plague” initially spread to much of Southern Europe due to unsanitary warfare and travel conditions, eventually reaching England and Moscow. It wasn’t until 1854 that the realization dawned that the Asian Cholera emerging in England was attributed to unhygienic drinking water.

In times when the existence of bacteria and germs was unknown, hygiene was linked to smell, and there was a belief that pleasant scents could cure diseases and prevent epidemics. Over the years, scientific studies have made significant strides in understanding viruses, bacteria, and the diseases they cause. In the mid-17th century, the Dutch merchant Anton van Leeuwenhoek made a groundbreaking discovery by proving the existence of living organisms invisible to the naked eye. In 1847, Ignaz Philip Semmelweis’s revelation that puerperal fever, leading to the death of women after childbirth or miscarriage, is caused by bacteria transmitted to the mother by the hands of clinical staff during childbirth marked a crucial turning point when hygiene became closely associated with health.

|

|

|

Max von Pettenkofer, Germany’s first professor of hygiene, established the Department of Hygiene in several universities in 1865, introducing a distinctive perspective to the field by pioneering the concept of “Social Hygiene” (Sozialhygiene). This concept emphasizes that bacteria are not the sole factor in the emergence of diseases, highlighting the role of social factors as well.

Many of the scientific studies made in the 1900s lay the foundation for contemporary research conducted in today’s state-of-the-art laboratories. The German physician Robert Koch, a Nobel Prize laureate in Medicine, is recognized as one of the pioneers of modern bacteriology. Meanwhile, the French chemist and bacteriologist Louis Pasteur, renowned for his work on fermentation and decay, as well as the development of rabies and anthrax vaccines, is considered the founder of microbiology. With the progress of modern medicine and science, the legacy of Hygieia undergoes a transformation, extending from Antiquity to the present day under the name of “hygiene”.

Hygieia |

Today, more than ever, we are contemplating and discussing hygiene in the light of Covid-19, which originated in Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei region, on December 1, 2019, and was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.

History reveals that hygiene is not achievable solely through individual efforts but is profoundly influenced by the society we inhabit and the environment in which we live. In this context, while science explores methods to combat viruses, the industry is actively pursuing more hygienic products, systems, and spaces through research and development studies. As we await the discovery of a vaccine, numerous design initiatives have emerged as pandemic measures. These include disinfectant units, masks, architectural interventions that shape public spaces in accordance with the social distancing rules, and contactless designs utilizing technology… While some of these designs offer temporary solutions, others present visions that will serve as the foundation for future research and studies, characterized by advanced R&D and finely crafted ideas. And they will accompany us in our pursuit of “hygiene” beyond the pandemic.

Designing Hygiene:

“Hi-Hygiene”

Hitit Seramik’s “Hi-Hygiene Technology” exemplifies the R&D activities conducted in the industry to create healthier and more hygienic spaces. Developed in Hitit Seramik laboratories through extensive R&D studies inspired by the hydrophobic and water-repellent feature of the lotus leaf, the “Hi-Hygiene Technology” prevents the formation of bacteria, mold, and fungi on porcelain and ceramic surfaces. This method, applicable to all Hitit Seramik tiles, stands out for its efficacy against both bacteria and fungi.

For those interested in delving into the history of hygiene and exploring hygiene’s connection to architecture and design, we recommend the 342nd issue of Arredamento Mimarlık magazine, themed as “Hygiene”. You can access the issue here.

For detailed information about Hitit Seramik’s “Hi-Hygiene Technology”, you can visit the “Hi-Hygiene” page.