The Third Life Between Two Passages and a Cul-de-Sac: İşbank Museum of Painting Sculpture

Photo: Cemal Emden, Courtesy of TEĞET.

Located between two passages and a cul-de-sac on İstiklal Street, the historic Boudouy (Bodvi) Apartment stands as a testament to Beyoğlu’s history, having lived three distinct lives within its century-long existence. In 2023, marking the 100th anniversary of the Republic, the building welcomed visitors as the İşbank Museum of Painting Sculpture, showcasing the bank’s extensive art collection amassed since its inception. This transformation into a museum was brought to fruition through a meticulous conservation approach by the TEĞET Architectural Office. Here, the architects tell the story of this new beginning.

Bodvi Apartment. Source: Arkitekt, 1954. |

Bodvi Apartment is a building that has experienced various transformations since its construction. Could you tell us about the functional and structural changes it underwent in its previous lives? Additionally, when did TEĞET encounter this building?

The life of the Bodvi Apartment Building begins in 1907, a time when Beyoğlu-Pera resembled Western cities of the era, and İstiklal Street was known as the Grand Rue de Pera, adorned with its array of shops, covered passages, apartment buildings, and entertainment venues. Constructed by the French merchant Joseph Baudouy, the building epitomizes the typical 19th century Beyoğlu apartment building. Ground and first floors are dedicated to stores, echoing the neighboring Carlmann’s Bon Marché. A clear demarcation between residential and commercial functions is established, delineated by the circulation structure. The apartments commence from the first floor, with entrances accessible from Perukar Çıkmazı Street (a cul-de-sac) on the Odakule Passage side.

As mid-century approaches, Beyoğlu undergoes a transformation, marked by drastic changes in its inhabitants and practices. The street and its edifices lose their former grandeur. However, the Bodvi Apartment Building, acquired by İşbank in the early 1950s, emerges from this period relatively unscathed. The second life of the building begins when it started to serve as the Beyoğlu branch of the bank and was referred to as the 4th Sigorta Han. The arched ground and first floors, once bustling stores, are revamped into a bank branch, marrying aluminum and glass with geometric lines on the façade, in harmony with the modernist architectural trends of the era. Within the building, the heavy and dense columns are being cut to expand the space and to reorganize it according to the new function, and a new axis of steel columns is being installed in their place. Offices occupy the upper floors, while the penthouse is repurposed as a cafeteria. Remarkably, the building’s integrity remains intact, save for alterations to the façade and structural adjustments on the ground and first floors.

4th Sigorta Han operates as a bank branch until the 2000s. TEĞET’s first encounter with the building takes place in 2015, following the bank’s decision in 2008 to reimagine the space as a museum showcasing collection artifacts.

Upon discovering the marble staircase hidden within the building during our initial visit, and after exploring the rooms with their lofty ceilings opening onto the street, we resolved to devise an approach aimed at preserving this building, which had borne witness to the events of the 20th century.

|

|

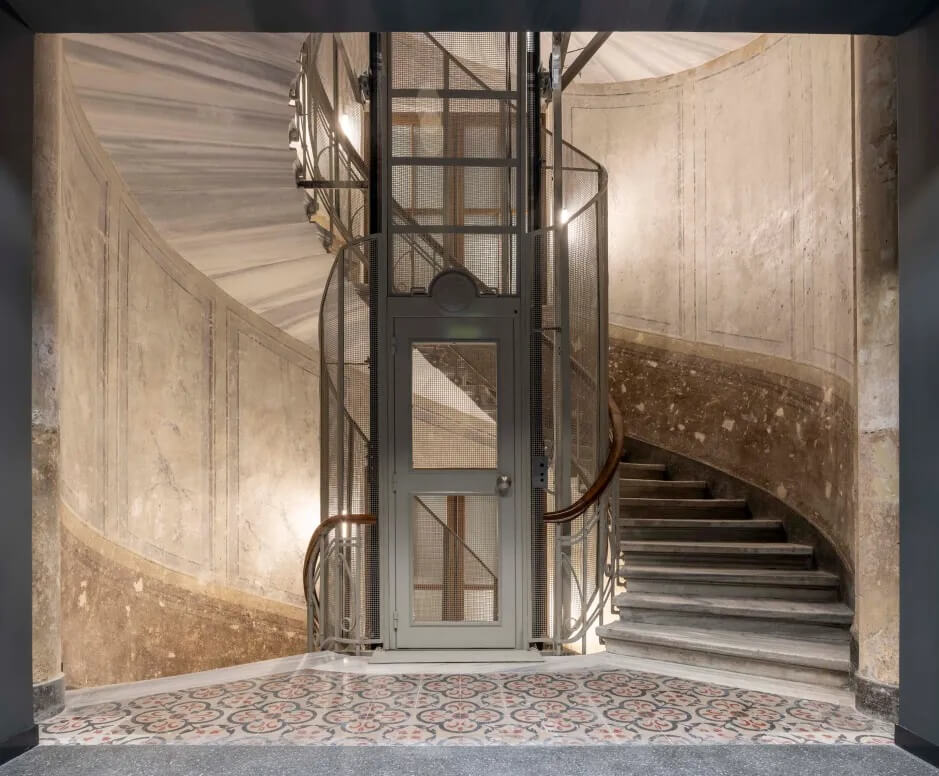

The staircase before (Photo: TEĞET) and after the restoration (Photo: Cemal Emden, courtesy of TEĞET)

When dealing with a centuries-old building, the project’s inception often finds itself at a crossroads: Should it be demolished, preserved, or simply repaired? Here, the choices made by both the client and the architect are as critical as the registration criteria or the building’s condition itself. What were the initial expectations of the client organization from you at the outset of the project? What degree of flexibility were you granted? How did your proposal to prepare the building for its third life begin to take shape?

When the project was presented to us, there was already an approved restoration plan endorsed by the board. This proposal, developed between 2010 and 2015, outlined a complete demolition and restoration of the building to its original state. Essentially, a reconstruction. Upon discovering the marble staircase hidden within the building during our initial visit, and after exploring the rooms with their lofty ceilings opening onto the street, we resolved to devise an approach aimed at preserving this building, which had borne witness to the events of the 20th century. We proposed a strategy that proved challenging to design and implement: preserving the original spatial organization, materials, and textures of the building’s primary axis, while incorporating a new structure inside to provide support to the historical exterior. We presented this concept to İşbank, which had been working on the transformation for approximately 6-7 years and had an approved board project. Fortunately, they embraced our conservation idea and supported the project with great sincerity.

|

|

Photos: By courtesy of TEĞET.

You proposed an unusual conservation approach for the building. It must have encountered countless problems at every stage of implementation, requiring numerous trials and on-site solutions. How was this design realized? What kind of difficulties and uncertainties did you encounter along the way?

The conservation approach of the project necessitated close interdisciplinary coordination, particularly between architecture and structural engineering. For example, we needed extensive collaboration with our civil engineer to devise a set of plans and strategies aimed at preserving the historic staircase. Positioned within what we refer to as the core structure, the staircase, with its final step reaching the first floor instead of the ground, had to be suspended in mid-air during construction to avoid any potential damage. Demolition, construction, and transformation activities proceeded simultaneously from various angles. A massive steel table was constructed beneath the staircase to provide support and also allowed for work on the shaft foundations. Many such steps involved thorough preparation and fabrication. Consequently, the workload exceeded that of typical construction sites. Only through these meticulous measures were we able to overcome the expected challenges without causing any damage.

On the other hand, decisions regarding the preservation and restoration of textures on both interior and exterior surfaces, which were either impossible or insufficient to determine during the project’s design phase or on paper, were made on-site. Solutions were devised based on the specific needs of textures that had worn out over the years or were concealed beneath other layers. Various on-site experiments were conducted to clean the stone and ornaments on the façade, and alternative methods were tested. It was only after careful consideration with the consultant teams that decisions were made to select and implement techniques aligned with the overarching conservation goals.

What excited us most during the construction process was the discovery of pencil drawings in the historic stairwell, which is now the heart of the building. Traces found beneath 7 layers of oil paint, along with a brown stripe at the parapet level and vertical frames, suit the museum’s ambiance better than any intervention we could envision today.

|

|

Hand-carved works discovered in the stairwell (Photo: TEĞET) and the stairwell after the restoration (Photo: Cemal Emden, courtesy of TEĞET)

An important aspect of the project is the building’s unearthed patina. During implementation, which layers of the building did you encounter from different periods? Which traces were you able or preferred to preserve until present day?

We say that the building had two previous lives before it became the Museum of Painting and Sculpture. Though these periods aren’t very distant, the building underwent some transformations in terms of both function and form. When formulating the conservation concept, we envisioned the building as it was originally constructed in the early 1900s, as a 19th century Beyoğlu apartment building. This included features such as the arched façade, a central circular marble staircase, wooden floors, and crown moldings on the ceiling. Over time, additional layers of materials were added, and interventions were made. Therefore, our primary objective was to unveil these layers. We achieved this by minimally intervening in the repair of stones, ornaments, crown moldings, and cement tiles, completing them where necessary without painting them, and solely applying a protective varnish. The stone façade of the ground and first floors on the İstiklal Street side was handled according to the restitution project.

On another note, what excited us most during the construction process was the discovery of hand-carved works in the historic stairwell, which is now the heart of the building. Traces found beneath 7 layers of oil paint, along with a brown stripe at the parapet level and vertical frames, suit the museum’s ambiance better than any intervention we could envision today. Today, the curvilinear surfaces of the stairwell adorned with pencil drawings stand as a testament to the building’s past lives and experiences.

The ground floor is bustling with public activities; the café, shop, and multipurpose hall are accessible to users beyond exhibition visitors. The Bodvi Apartment welcomed not only its owners but also passersby on the Grand Rue de Pera a century ago, and this is still true today.

Photo: Cemal Emden, Courtesy of TEĞET. |

The museum made a significant contribution to the accessibility of culture and art by offering free admission to its collection for the first two months, attracting over 40 thousand visitors during this period. How does the architecture of the building engage in a dialogue with the city and its visitors?

The museum is situated on İstiklal Street, right next to Odakule Passage. Beyoğlu, and İstiklal Street in particular, is not only historically and culturally significant but also a hub with extremely high pedestrian traffic. The museum’s ability to tap into these potentials is evident from the persistent lines at its door, particularly on weekends.

Photo: Cemal Emden, Courtesy of TEĞET. |

The interaction between visitors and the building is influenced by both the building’s program and the exhibition narrative. The ground floor is bustling with public activities; the café, shop, and multipurpose hall are accessible to users beyond exhibition visitors. The Bodvi Apartment welcomed not only its owners but also passersby on the Grand Rue de Pera a century ago, and this is still true today. In the exhibition areas on the upper floors, visitors can explore artworks from the same period as the historical building they are in, thus enabling them to evoke the atmosphere of that era to some extent. Moreover, by crossing the threshold between the historic and the new building, visitors can engage in a more intimate dialogue with the structure, freeing themselves from the weight of nostalgia and historical significance, much like how the low and dark gallery is enlivened by spaces offering diverse perspectives.