Everything at Once: Return to the Postmodernity

SITE (James Wines), “Highway 86”, Vancouver World’s Fair, 1986; © SITE - James Wines, LLC

The year 1967 is a turning point: it marks the beginning of the abandonment of modernism, which assumed that almost every issue could be solved by equal rights and opportunities for all, and of the birth of a new and eccentric world. Designers throw off the yoke of established conventions of taste, while architects declare the amusement park to be the new ideal model of the city, and an era is ushered in where form follows fun, not function. The conflict between two dominant political systems gives way to a fight for self-realization. New media synchronizes the world, and the visual world becomes an arena for style and recognition races.

The exhibition “Everything At Once: Postmodernity, 1967-1992”, hosted by the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, revives the spirit of postmodernism from the ‘60s to the ‘90s with a narrative that feeds upon numerous fields. The exhibition, consisting of seven sections, narrates the beginning of the information society, the deregulation of financial markets, and the golden age of subcultures with disco, punk, and techno-pop through striking examples from design, fashion, music, architecture, cinema, philosophy, art, and literature. This was also a period when cultural bastions were established one after another; therefore, one of the displayed objects is the host museum itself, the Bundeskunsthalle. In 1992, when it was founded, the Cold War had ended, and Francis Fukuyama had declared the “end of history” in his famous book.

The exhibition also questions, by holding up a mirror to our present, where we are encouraged through social media to the renaissance of postmodern aesthetics, and where designers and architects are reorienting towards postmodern ideas of diversity, contradictions, and decentralization: Has the postmodern era come to a close, or are we still within it?

The Awakening of the Media

In 1969, man sets foot on the Moon for the first time. The entire world witnesses this moment on their televisions; after all, more and more people now have televisions in their homes. In the 1970s, people’s dreams center around a life in soap bubbles, free from the weight of modern architecture. The focus is more on the self than on politics. Communication becomes more challenging, texts detach from content, ideas surpass objects, and design takes precedence over function. The world is entering a new era of free-floating exchange rates...

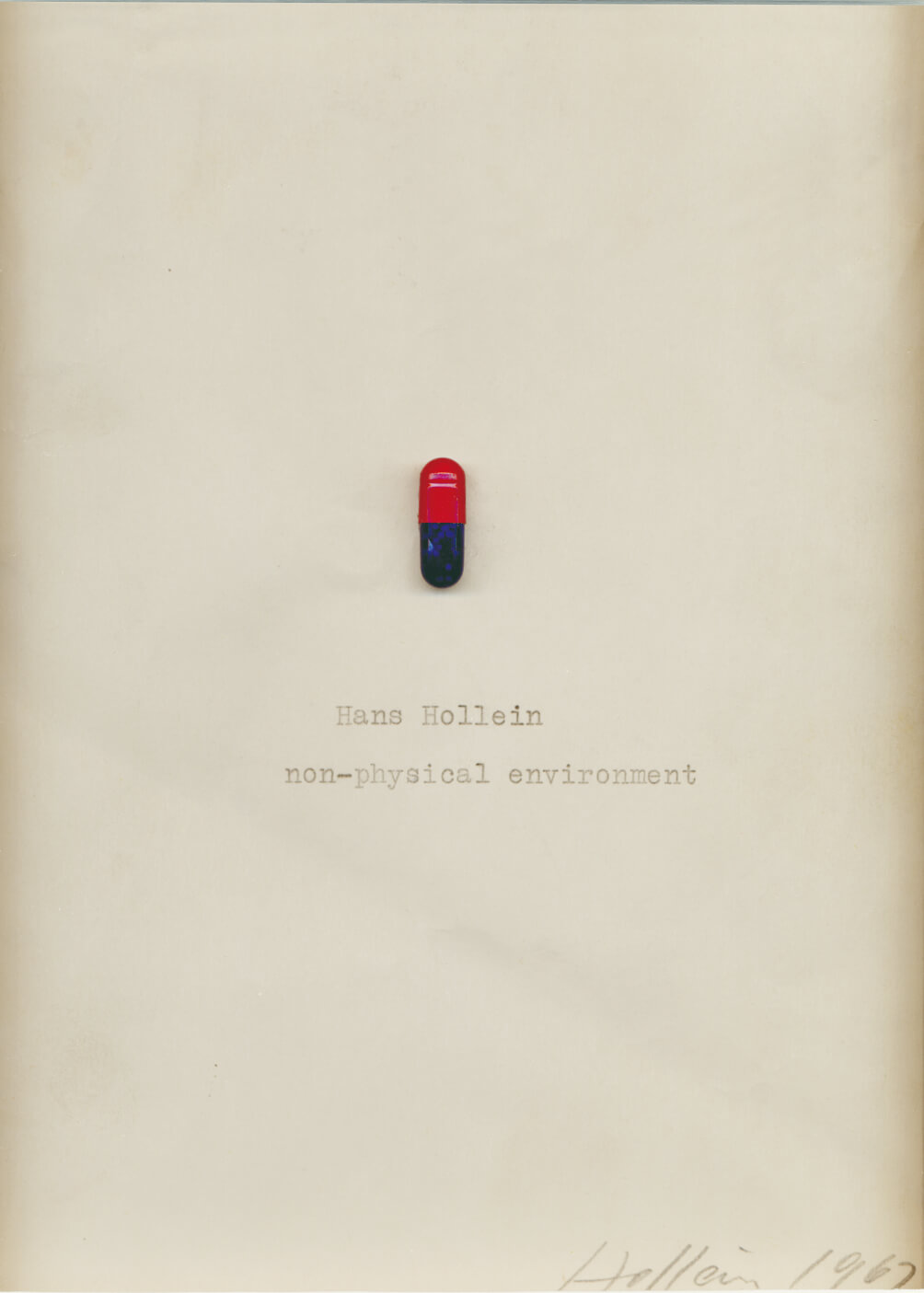

Hans Hollein, “Non-physical environment”, the Architecture pill, 1967 © Hollein Archive |

In 1967, the Austrian architect and designer Hans Hollein glued a real pill onto a piece of paper and wrote his name, the date, and the word “Architecture” underneath. These “architecture pills”, integral to his project “Nonphysical Environmental Control Kit”, constitute a set proposing the creation of various desired environmental states. With this work, supporting the manifesto “Everything is architecture” while simultaneously treating architecture as a kind of disease, Hollein suggested that the problematic relationship between human beings and architecture should be radically rethought.

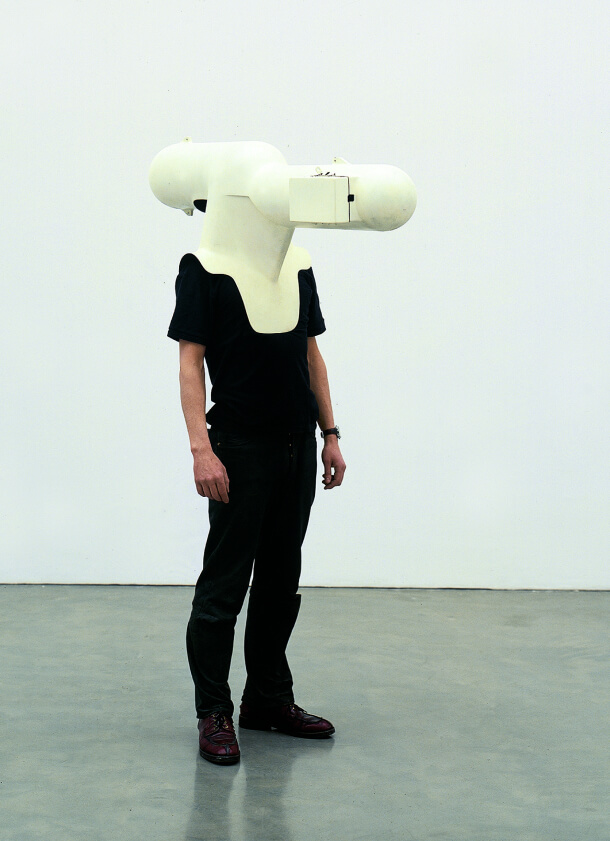

TV Helmet (Portable Living Room) designed by Walter Pichler, 1967; © Generali Foundation, Photo: Werner Kaligofsky |

The TV Helmet, designed by the architect and artist Walter Pichler in the same year, functions as a technical device that ensnares the user in an infinite information network, rendering them completely isolated from the outside world. Called the “Portable Living Room”, this invention not only formally anticipates the cyber-glasses developed decades later but also prompts contextual questions about the media experience preceding the exploration of the “virtual world”. Positioning amongst the realms of design, architecture, and art, Pichler’s TV Helmet prototypes can be seen as life balloons, seeking answers to the questions surrounding the individualized life of the future...

The Ruins of Modernism

It’s 1972. The death of modernism has been declared, and its buildings are being blown up both on screen and in reality... The era of terrorism begins, ushering in a decade marked by economic and political uncertainty. The limitations of growth are laid bare. Design undergoes radicalization, a period where chairs are set ablaze, and comfort is no longer sought in armchairs. The modern age transforms into a quarry, where the violation of style becomes the norm. The vibrant signage of Las Vegas emerges as the new architectural role model.

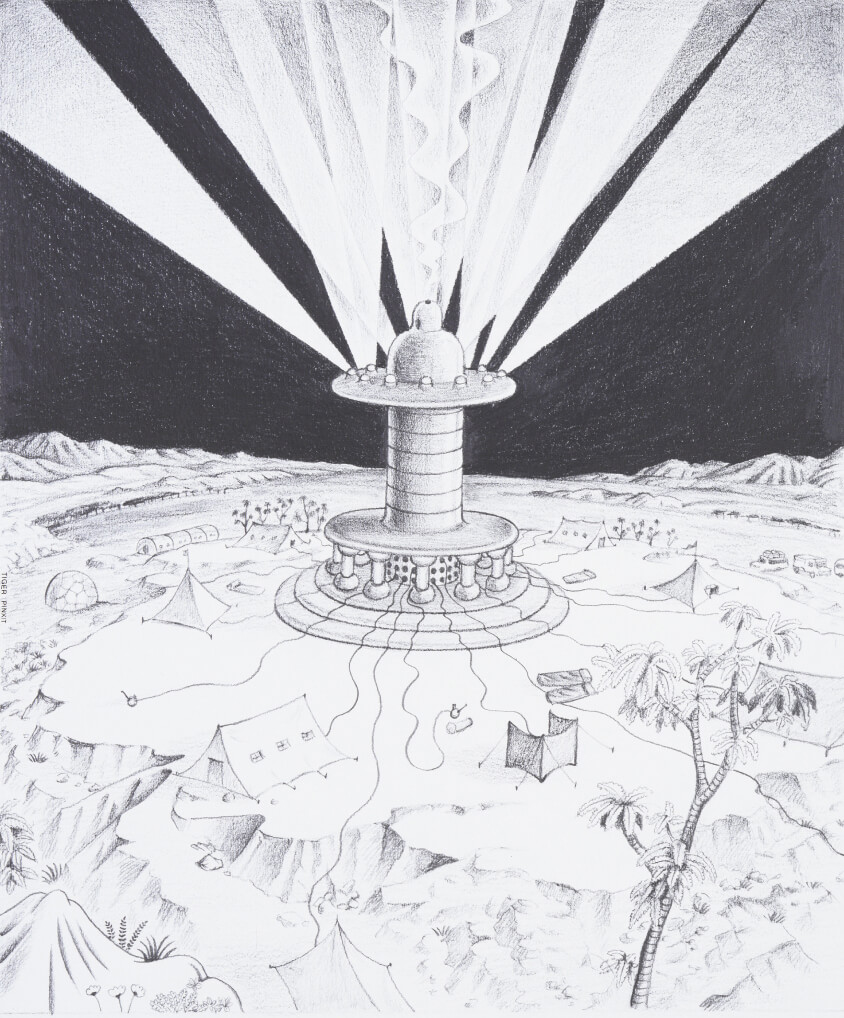

Ettore Sottsass, “The Planet as Festival”, perspective drawing, 1972-1973; © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, The Museum of Modern Art / Scala, Florence |

In his 1972-73 series of sketches titled “The Planet as Festival”, Ettore Sottsassi, a pioneer of radical design, juxtaposes a psychedelic Martian landscape against a backdrop of crumbling cities. These drawings, illustrating the transformation of life in Western countries into a festival as desires suppressed by modernism are unleashed in the postmodern age, also foreshadow the “experience economy”, predicted by Alvin and Heidi Toffler in their renowned book Future Shock. The Tofflers anticipated a significant proportion of experiential products providing simulated environments, offering users a taste of adventure, danger, and other pleasures without risking their real-life or reputation.

The furniture designs of Archizoom Associati, such as the Sanremo floor lamp (1968) and the Mies chair and ottoman (1969), alongside the seminal multimedia performance Media Burn (1975) by Ant Farm and SITE’s (James Wines) Cutler Ridge Building (1979), are other noteworthy works featured in this section.

Everything is Acceptable

By 1978, from politics to urban planning, in both theory and practice, everything is liberated, everything is rational… Furniture on one hand, and public buildings on the other, are shaped by exotic fantasies. Postmodernism now implies the art of combining elements in novel ways, and the distinctions between near and far begin to blur. Ironic distance replaces the existential seriousness. The individual becomes the paramount criterion, with being exceptional becoming fashionable.

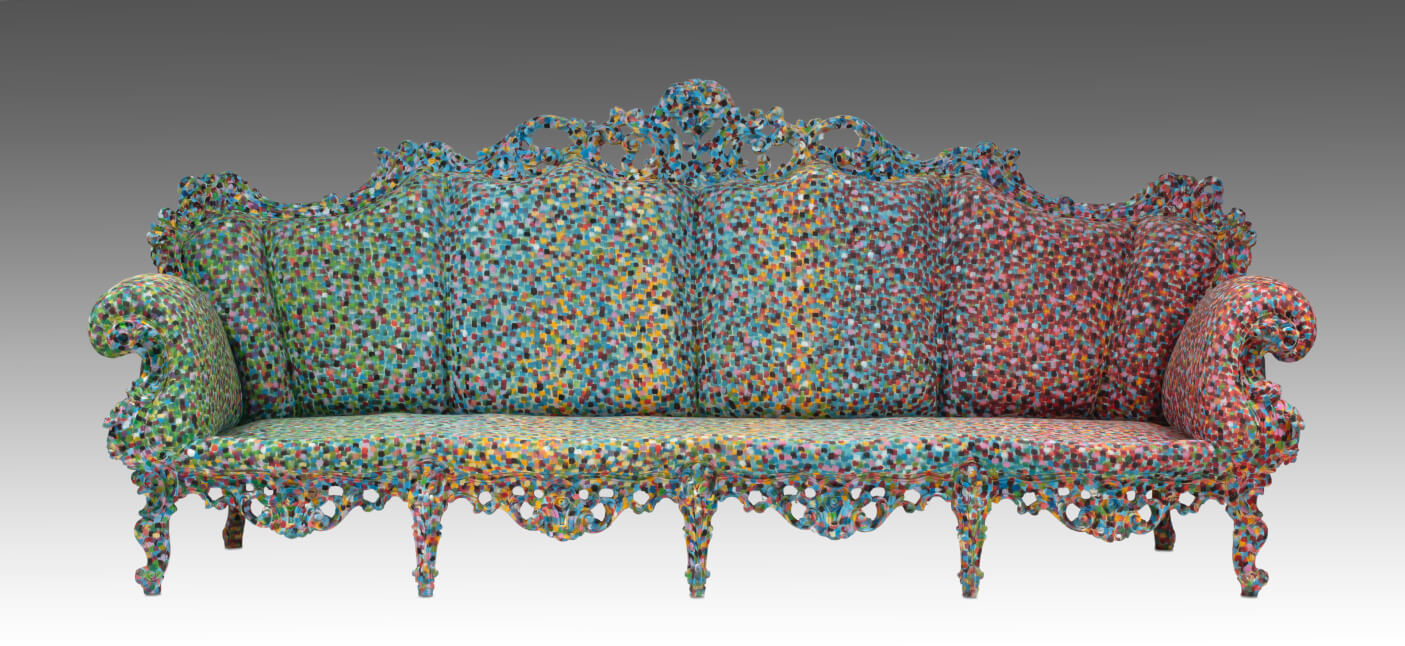

Alessandro Mendini, “Interno di un interno” (Sofa), 1990; © Collection Groninger Museum, Photo: Heinz Aebi |

In this section, notable examples include the sofa designs by Alessandro Mendini, a pioneer in the development of postmodern design in Italy who skillfully combines baroque forms with the dotting technique. Renowned for both his ironic objects and distinctive structures, Mendini has played a significant role in fostering a critical approach to postmodern design through his editorial experience at Casabella, Modo, and Domus magazines.

Masanori Umeda (Memphis Milano), “Tawaraya-Ring”, Boxing ring 1981; © by courtesy of Memphis Milano |

The Tawaraya Boxing Ring (1981), designed by Masanori Umeda of Memphis Milano, stands out as one of the most iconic works of the period. Designed as furniture that transforms into space, the ring features five tatami, symbolizing the interiors of traditional Japanese homes. In this work, Umeda uses boxing as a metaphor in his quest to establish a dialogue between East and West.

Protect Me From What I Want

The modern era preached “Follow the rules if you want to get somewhere”. In postmodern times, this slogan has been replaced by “Be yourself and do something for yourself”. Emotions are no longer suppressed; instead, they become a source that feeds commercials, movies, and pop music.

The title of this section, “Protect Me From What I Want”, is a plea by Jenny Holzer, one of the conceptual artists at the forefront of the feminist wave of the 1980s. In her 1982 installation, this sentence, written with LED lights, appeared among the advertisements on the giant screen of Times Square.

General Idea, “Pasta Paintings: Untitled (Mastercard)”, 1986-1987; © Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg |

The pasta paintings by the General Idea collective in the series “Pasta Paintings” (1986-87) transform commercial emblems into “empty” geometric abstractions, distancing them from their original meanings. Renowned for their artworks challenging the commodification of art, the group showcased their detachment and response to high art through installations in public spheres.

The “Constructivist Maternity Dress” (1980), designed by Jean-Paul Goude in collaboration with the fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez for the singer and model Grace Jones, Michel Foucault’s letter to Simeon Wade in 1976, and the Palladium Nightclub (1985), designed by the architect Arata Isozaki and constructed inside an old theater in New York, are some of the pieces that stand out in this section...

Nothing Is Real

1980: As standards are abandoned, the now-questionable reality is replaced by the media, and grand narratives give way to speculation. The end of reality means the removal of all barriers. Concurrently with the stock markets, there is an explosion in postmodern architecture adorned with rococo ornaments, columns, and capitals. History transforms into visual witticisms that today we call “memes”. Buildings become data carriers, much like people. Personal expression yields to cool poses. We find ourselves at the dawn of the hyperspace age, where the increasing data processing power allows for ever-more individual solutions, optimized production processes, and everyday realities that are increasingly isolated from each other.

Cindy Sherman, “Untitled Film Still #25”, 1978; © Private collection, by courtesy of Sprüth Magers. |

In her series “Untitled Film Stills”, Cindy Sherman, the American photographer and film director of the prominent female figures of the era, creates imaginary yet strikingly familiar movie scenes. Portraying generic female characters, Sherman, who appears in the photographs herself, blurs the boundaries of reality while questioning the stereotypical roles assigned to women.

Culture and Capital

As the social state is being dismantled in the late 1970s, the idea of economic justice gives way to cultural participation. Culture becomes a tool of capital and a value one must possess just like currency. Many individuals who feel excluded from the educated cosmopolitan life begin to demand a return to the “traditional values”.

Models in front of the Staatsgalerie designed by James Stirling & Michael Wilford and Associates, Stuttgart, Germany, 1980s; © James Stirling/Michael Wilford, Canadian Centre for Architecture (Montréal) Collection |

Museums and libraries proliferate rapidly, as exemplified by the inauguration of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Designed by Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, and Gianfrancho Franchini, this building, with its inverted design, garners exponentially increasing interest from its construction phase. Another icon of postmodern architecture is the Neue Staatsgalerie, designed by James Stirling in collaboration with Michael Wilford and Associates. Beyond its use of materials and colors, it injects a breath of fresh air into museum architecture by boldly addressing the old-new conflict through its interaction with the historical building to which it is an addition.

Aldo Rossi, “Tea & Coffee Piazza”, 1983; © Collection Groninger Museum, Photo: John Stoel |

Like many luxury brands, Alessi’s products, too, bear the signature of the leading architects, designers, and artists of the era. In the brand’s “Tea & Coffee Piazza” project, accomplished with 11 invited designers, coffee cups transform into decorative columns (Charles Jencks), a structure in the city square (Aldo Rossi), and an aircraft carrier (Hans Hollein).

The End of History

1989: What remains of postmodernism as the Cold War draws to a close? Has it become merely a decorative element adorning the streets, as seen at the International Building Exhibition in Berlin? Humanity dreamed of the metaverse before the Internet. The invention of the blue LED paved the way for smartphones.

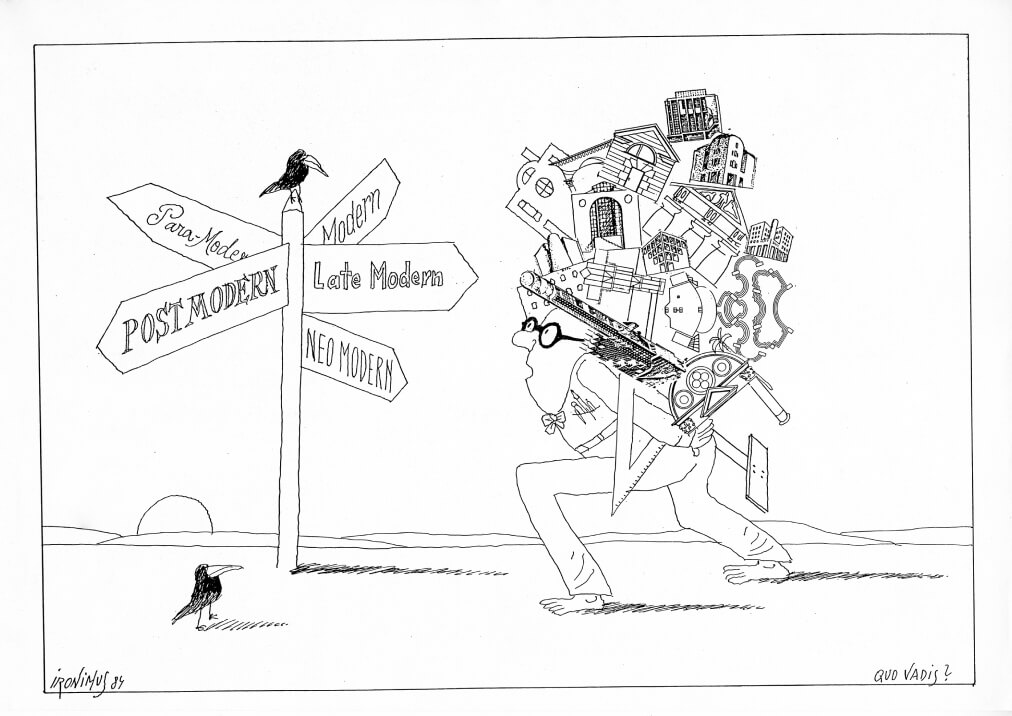

Gustav Peichl, “Quo vadis?”; © Scan: Crone Wien GmbH |

The Bundeskunsthalle, which hosts this exhibition, is one of the buildings that made the architect Gustav Peichl famous. Peichl, also a caricaturist, stands out as a prominent figure of the movement but rejects the postmodernist label. Nevertheless, just like the overcoming of resistance to stylistic boundary violations, these contradictory responses were accepted as an integral part of postmodernism.

The design of the exhibition, curated by Eva Kraus and Kolja Reichert, brings the postmodern city into the museum space with roads, silhouettes, facades, and giant billboards. The architect Nigel Coates and the graphic designer Neville Brody created this universe within the galleries. In Brody’s words, “Designing a world that reflects the postmodern spirit is no easy task”. A universe that meanders like wormholes and revels in contradictions...

|

|

|

|

View from the exhibition; © Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland GmbH, Photos: Roman März, 2023

A book with the same title was published in parallel with the exhibition. The book, prepared for publication by the curators and as colorful as the exhibition itself, includes essays by Nikita Dhawan, Diedrich Diederichsen, Oliver Elser, Gertrud Koch, Eva Kraus, Sylvia Lavin, Kolja Reichert, Lea-Catherine Szacka, and many others, along with a wealth of visual material.

“Everything At Once: Postmodernity, 1967–1992” will be open to visitors until January 28, 2024.